Ok, I just wanted to make sure I got this flask thing figured out. Here’s what I did and what happened when I did it.

First I made a directory to house my test site. It’s as follows:

c:\code\test\mysite

I then enter that directory to make sure any commands I do take place within it. I need a virtual environment to house Flask. When I install Flask, I don’t want to do it system-wide. This part was pretty simple too:

virtualenv venv

(Remember, the venv at the end is just the name of the directory the virtualenv will be installed into. You can actually name it anything you want, but venv is standard practice.) After creating the virtual environment, I need to enter it. I do this by running the activate script in the Scripts sub-directory:

venv\Scripts\activate

The prompt now changes to show that the virtual environment is active. If I wish to exit the virtual environment, all I need to do is type deactivate. Finally, I need to install Flask into the virtual environment using pip. This is quite simple:

pip install flask

Boom! All done! Flask is installed into a virtual environment and ready to use. I should note that the file structure here is different from the one noted in Miguel Grinberg’s Flask tutorial. Miguels says that the file structure should look like this:

microblog\

flask\

<virtual environment files>

app\

static\

templates\

__init__.py

views.py

tmp\

run.py

But I find that mine looks like this:

mysite\ venv\ include\ Lib\ __pycache__\ collections\ distutils\ encodings\ importlib\ site-packages\ flask\ <other packages> Scripts\

I can think of a few reasons why this might be. For starters, this entry was last updated in September 2014. About a year ago. Flask may have changed a lot since then. Another reason for the difference might be that I’m doing this on Windows and Miguel was doing it on Linux and they change things between systems. I will have to investigate this more and find out why there are discrepancies.

EDIT: Aha! I found one of the discrepancies! In the tutorial, Miguel uses the command virtualenv flask instead of virtualenv venv. That would explain why he has a folder titled “flask” in his microblog directory.

Here’s the purpose of the other folders he created:

The

appfolder will be where we will put our application package.

Thestaticsub-folder is where we will store static files like images, javascripts, and cascading style sheets.

Thetemplatessub-folder is obviously where our templates will go.

And here are the files that he created:

__init__.py

from flask import Flask app = Flask(__name__) from app import views

The __init__.py file’s purpose is to create the application object (of class Flask) and then import the views module. The views are the handlers that respond to requests from web browsers or other clients. In Flask handlers are written as Python functions. Each view function is mapped to one or more request URLs.

views.py

from app import app

@app.route('/')

@app.route('/index')

def index():

return "Hello, World!"

The function in the views.py file just returns a string, to be displayed on the client’s web browser. The two route decorators above the function create the mappings from URLs / and /index to this function.

run.py

#!flask/bin/python from app import app app.run(debug=True)

The run.py script starts up the development web server with our application. It imports the app variable from our app package and invokes its run method to start the server.

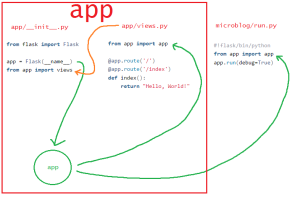

Finally, I should mention that I am a very visual learner, so the following drawing is my understanding of what’s happening when you enter flask\Scripts\python run.py:

Just a final note on the __init__.py file: The __init__.py file makes Python treat directories containing it as modules. Furthermore, it is the first file to be loaded in a module, so you can use it to execute code that you want to run each time a module is loaded, or specify the submodules to be exported. It allows you to define any variable at the package level. Doing so is often convenient if a package defines something that will be imported frequently.

EDIT: One more thing! The first line of the run.py file was enigmatic for me. I finally found out that it is a shebang line. I’ll have to do more research on its purpose.